Bangladesh Crypto AML Enforcement: Rules, Risks & Reality

Bangladesh Crypto Legal Status Checker

- Foreign Exchange Regulations Act, 1947 FX

- Anti-Money Laundering Act, 2012 AML

- ICT Act Tech

- Income Tax Ordinance, 1984 Tax

Quick Takeaways

- Bangladesh relies on existing AML and foreign‑exchange laws to clamp down on crypto, rather than a dedicated digital‑asset statute.

- The Bangladesh Bank, Ministry of Finance, and the Financial Intelligence Unit lead enforcement, with the CID handling prosecutions.

- Mining is explicitly illegal; trading, possession and use are discouraged under the 1947 Foreign Exchange Regulations Act and the 2012 AML Act.

- Recent arrests (2024) show that authorities actively monitor underground mining farms and large‑scale exchanges.

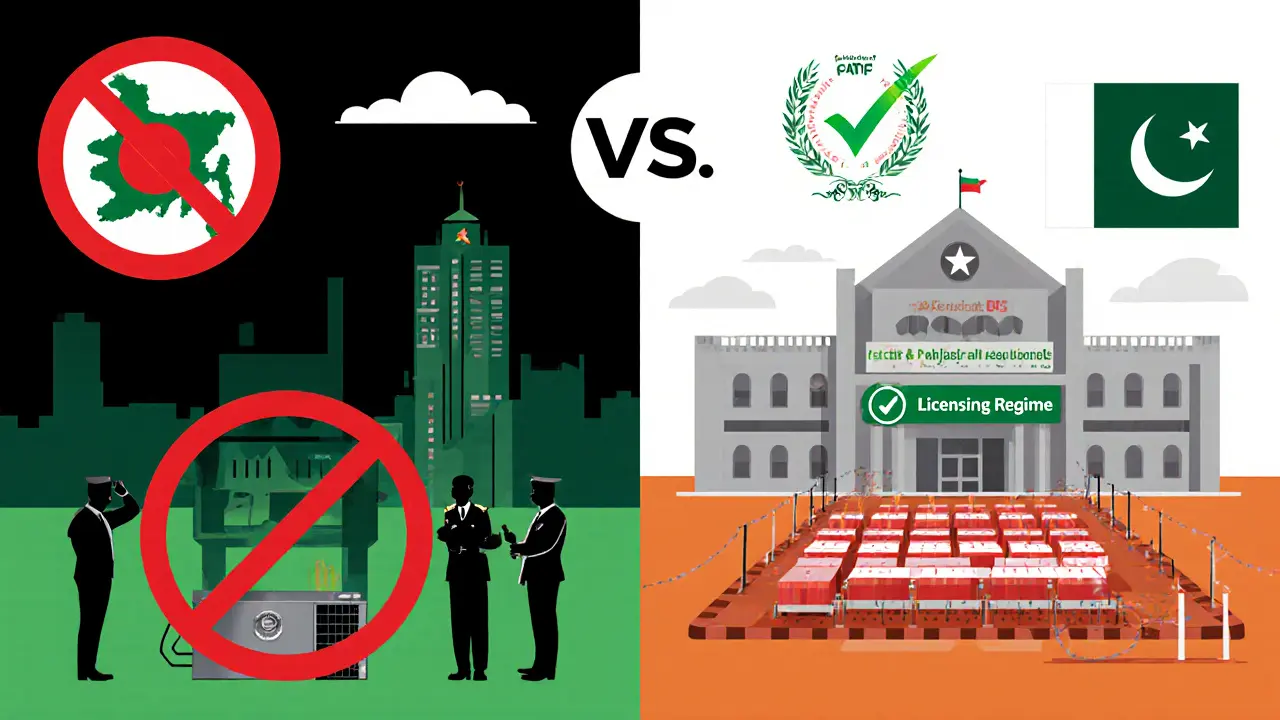

- Regional contrast: Pakistan has created a dedicated Digital Assets Authority, highlighting Bangladesh’s isolation in South‑Asia.

When it comes to anti‑money‑laundering crypto enforcement in Bangladesh the country applies a strict, largely implicit ban on virtual assets and uses existing financial laws to prosecute illicit activity, the landscape can feel like a maze. Below we break down who enforces the rules, which laws apply, how enforcement has evolved, and what the future might hold for crypto users and businesses.

Key Regulators and Their Mandates

Bangladesh Bank the central bank and primary watchdog for all financial transactions in the country has issued the most frequent public warnings since 2014, labeling crypto as a threat to financial stability. Its directives are relayed to the Criminal Investigation Department (CID) the law‑enforcement arm that prosecutes violations of AML and foreign‑exchange rules.

The Ministry of Finance sets national fiscal policy and can introduce new crypto‑specific legislation currently influences the regulatory tone but has not yet drafted a dedicated act. Meanwhile, the Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) collects and analyses suspicious transaction reports, including those involving digital wallets plays a critical role in flagging potential money‑laundering activity.

Legal Framework Used for Enforcement

Bangladesh operates without a standalone crypto law. Instead, authorities invoke several older statutes:

- Foreign Exchange Regulations Act, 1947 governs cross‑border currency movements; crypto transactions are treated as illegal foreign‑exchange activity.

- Anti‑Money‑Laundering Act, 2012 defines prohibited financial conduct and sets reporting obligations for banks and FIUs.

- Information and Communication Technology (ICT) Act covers misuse of digital platforms; authorities cite it when shutting down illegal mining rigs.

- The National Board of Revenue (NBR) applies the general Income Tax Ordinance of 1984 to crypto gains, despite the lack of a crypto‑specific tax code.

Because these acts were not drafted with digital assets in mind, enforcement often hinges on interpretation, creating legal uncertainty for users and businesses.

Timeline of Enforcement Actions

- 2014: Bangladesh Bank’s first public warning against Bitcoin, citing potential money‑laundering risks.

- 2016: Follow‑up circular warning that crypto could breach the 1947 and 2012 statutes.

- 2017: Official statement declaring crypto “illegal” due to AML and terror‑finance concerns.

- 2020: National Blockchain Strategy acknowledges blockchain for government services but does not alter the crypto stance.

- 2024: Series of raids in Dhaka result in multiple arrests of clandestine mining operators; CID files charges under the AML Act.

- 2025 (present): Ongoing monitoring by FIU; no new crypto‑specific legislation introduced.

How Enforcement Works on the Ground

Enforcement follows a multi‑step process:

- Surveillance: FIU receives Suspicious Transaction Reports (STRs) from banks and telecom firms. Crypto‑related wallet addresses, especially high‑volume TRC20 and BEP20 wallets, trigger alerts.

- Investigation: CID teams, often with cyber‑forensics support, trace IP logs, electricity usage spikes, and social‑media chatter to locate mining farms.

- Legal Action: Offenders are charged under the AML Act for “money‑laundering through virtual assets” and under the ICT Act for “unauthorised use of computer resources.” Penalties range from fines (up to 2million BDT) to imprisonment (up to 7years).

- Asset Seizure: Physical mining equipment and crypto holdings are confiscated. In 2024 raids, authorities seized over $1.2million worth of Bitcoin and associated hardware.

The emphasis is on the AML angle-ownership alone is not always punishable, but any transaction that moves value across borders or disguises illicit proceeds is prosecuted.

Compliance Challenges for Crypto‑Related Businesses

If you operate a crypto exchange, wallet service, or mining operation that targets Bangladeshi users, you face several hurdles:

- Licensing Void: No legal framework to obtain a crypto‑exchange licence; the only path is to register as a foreign‑exchange bureau, which is prohibited for crypto.

- AML/KYC Burden: You must implement Know‑Your‑Customer (KYC) checks to the standard of the AML Act, despite the lack of a clear regulator for verification standards.

- Reporting Obligations: All suspicious activity must be reported to the FIU within 30days; failure can result in corporate fines.

- Tax Ambiguity: The NBR treats crypto gains as regular income, but no clear guidance on valuation methods (fair market value, cost basis, etc.) exists.

Non‑compliance can quickly attract the CID’s attention, especially if transaction volumes exceed the threshold of 10million BDT in a single month.

Regional Comparison: Bangladesh vs. Pakistan

| Aspect | Bangladesh | Pakistan |

|---|---|---|

| Primary Regulator | Bangladesh Bank | Pakistan Digital Assets Authority (PDAA) |

| Legal Status of Crypto | Implicitly banned; enforcement via AML & FX laws | Legally recognised; licensing regime for exchanges and miners |

| Mining Policy | Explicitly illegal under ICT Act | Strategic reserve of 2,000MW allocated for Bitcoin mining |

| FATF Alignment | Partial - gaps in Recommendation15 (VA regulation) | Full compliance roadmap announced 2025 |

| Enforcement Examples (2024‑25) | Arrests of underground mining farms; confiscation of $1.2M crypto | Licensing of 12 exchanges; tax incentives for compliant miners |

Future Outlook and Possible Reforms

Several forces could reshape Bangladesh’s crypto stance:

- International Pressure: Ongoing FATF assessments may compel the government to draft a dedicated Virtual Asset Service Provider (VASP) framework.

- Economic Incentives: Neighboring countries are tapping into crypto revenues; Bangladesh could miss out on fintech investment if it stays rigid.

- Technology Adoption: The 2020 National Blockchain Strategy shows willingness to use blockchain for public services, hinting at a possible split‑track approach - blockchain allowed for government, crypto restricted for private use.

- Domestic Advocacy: Crypto‑focused startups and NGOs are lobbying the Ministry of Finance for a clear licensing path, citing job creation and remittance benefits.

Until such reforms materialise, the safest route for anyone dealing with digital assets in Bangladesh is to treat all crypto activity as if it falls under the AML Act and the 1947 FX regulations.

Key Takeaways for Practitioners

- Assume crypto transactions are prohibited unless you have explicit government approval.

- Implement robust AML/KYC procedures that meet the standards of the 2012 AML Act.

- Monitor FIU advisories; they often signal upcoming enforcement focus.

- Consider alternative jurisdictions for crypto‑related business if you need a legal operating environment.

- Stay updated on FATF assessments - non‑compliance could trigger stricter penalties.

Frequently Asked Questions

Is owning Bitcoin illegal in Bangladesh?

Ownership itself is not expressly outlawed, but any transaction that moves value across borders or attempts to conceal source of funds is prosecuted under the AML Act, effectively making practical use illegal.

Can a company obtain a license to run a crypto exchange?

No dedicated exchange licence exists. The only legal path would be to register as a foreign‑exchange bureau, which the Bangladesh Bank prohibits for crypto activities.

What penalties can miners face?

Mining is explicitly illegal under the ICT Act. Convicted miners have faced up to 7years imprisonment and fines exceeding 2million Bangladeshi Taka, plus seizure of hardware and any crypto holdings.

How does the FIU detect crypto‑related money laundering?

The FIU analyses STRs from banks, telecom data on mobile‑money transfers, and electricity‑usage patterns that suggest hidden mining operations. It also collaborates with cyber‑forensics units to trace blockchain addresses linked to suspicious activity.

Will Bangladesh eventually adopt a crypto‑friendly regulatory framework?

Experts expect pressure from FATF and regional competition to push the government toward a VASP licensing regime, but any change is likely to be gradual and will retain strong AML safeguards.

Jack Stiles

Man, the Bangladesh scene looks like a wild west of crypto bans and AML scares – kinda crazy how they treat mining like it’s a crime scene.

Ritu Srivastava

It is absolutely reprehensible that a nation would stifle financial innovation while hiding behind vague AML rhetoric; citizens deserve transparency and fairness, not arbitrary crackdowns.

Liam Wells

One might argue that the existing statutes, albeit archaic, provide a sufficient framework for deterrence; however, the overreliance on the 1947 Foreign Exchange Regulations Act evidences a regulatory myopia, neglecting the nuanced technological realities of blockchain; consequently, enforcement becomes a blunt instrument rather than a precise scalpel, which, in my estimation, undermines both legal certainty and economic development.

Caleb Shepherd

What they don’t tell you is that the whole AML push is a front for a larger power play – hidden actors want to control the flow of capital and keep the digital rebels in check.

Don Price

The narrative presented by Bangladesh’s regulators reads like a cautionary tale ripped from a Cold War manual, wherein every piece of hardware humming in a basement is instantly labeled a threat to national security; meanwhile, ordinary individuals who merely hold a wallet are left in a legal limbo, forced to navigate a labyrinth of statutes that were never drafted with digital assets in mind; this creates a chilling effect that dissuades legitimate entrepreneurial activity; the penalties outlined – up to seven years imprisonment and multi‑million BDT fines – are disproportionately harsh for offenses that, in many other jurisdictions, are treated as civil infractions; such severity suggests a punitive mindset rather than a corrective one; if the aim truly is to curb money laundering, a nuanced, risk‑based approach would be far more effective than blanket bans; ultimately, the policy appears more about projecting authority than fostering financial integrity.

Dawn van der Helm

Wow, this is so intense! 🙌 It feels like Bangladesh is walking a tightrope between protecting its economy and stifling innovation. 🌐 Keep an eye on how the FIU evolves – maybe there’s a silver lining ahead. 😊

Monafo Janssen

From a cultural standpoint, it's fascinating how the government leans on legacy laws to address a modern technology; perhaps a dialogue between tech communities and regulators could bridge the gap.

Michael Phillips

It raises a philosophical question: should the state dictate the tools of exchange, or merely safeguard against abuse? The balance is delicate, and Bangladesh seems to be tipping toward the former.

Jason Duke

The current enforcement feels heavy‑handed; we need smarter, proportional measures! Otherwise, innovation will simply flee the country.

Bryan Alexander

Imagine a future where miners hide in basements, whispering about the next big hash while the authorities knock on doors – it’s the drama of a digital Wild West!

Patrick Gullion

Honestly, the whole thing feels overblown; sure, there are risks, but banning everything isn’t the answer.

Mark Bosky

Bangladesh’s reliance on the Foreign Exchange Regulations Act of 1947 to suppress crypto activity illustrates a legislative lag that hampers technological adoption. The Act, conceived in a pre‑digital era, lacks the definitions required to differentiate benign wallet holdings from illicit money‑laundering operations. Consequently, banks and financial institutions are left to interpret ambiguous guidance, leading to inconsistent enforcement across the country. The Anti‑Money‑Laundering Act of 2012 adds another layer of complexity, imposing reporting obligations that are difficult to satisfy without clear crypto‑specific protocols. Moreover, the ICT Act’s prohibition of mining fails to consider that many small‑scale miners operate within legal electricity consumption thresholds. This patchwork of laws creates a regulatory gray zone where businesses cannot reliably assess compliance risk. In practice, the Criminal Investigation Department has conducted raids that result in asset seizures, yet the legal aftermath often stalls due to procedural uncertainties. Investors, both domestic and foreign, perceive this as a hostile environment, deterring capital inflows that could otherwise stimulate fintech growth. The lack of a dedicated Virtual Asset Service Provider (VASP) licensing regime also prevents the establishment of regulated exchanges, pushing users toward unregulated offshore platforms. While the Bangladesh Bank issues frequent warnings, these statements do not substitute for a coherent statutory framework. International bodies such as the FATF have highlighted these gaps, urging member states to develop comprehensive crypto regulations. Without legislative reform, Bangladesh risks falling behind regional competitors like Pakistan, which has already instituted a Digital Assets Authority. The economic opportunity presented by blockchain–based remittances and decentralized finance is substantial, especially for a diaspora‑driven economy. Ignoring this potential may result in lost tax revenue and diminished innovation capacity. Therefore, a balanced approach that integrates AML safeguards with clear licensing pathways is essential for sustainable development.

Ken Pritchard

Great analysis, Mark. For anyone navigating this space, my advice is to maintain meticulous records and stay updated on FIU advisories – that’s the safest path forward.

Brian Lisk

Building on Ken’s point, it is imperative to adopt a comprehensive compliance framework that not only satisfies the AML reporting thresholds but also anticipates future regulatory shifts; this includes implementing robust KYC procedures, continuous transaction monitoring, and periodic internal audits, all documented in a manner that aligns with both domestic statutes and emerging international standards, thereby reducing exposure to punitive actions while fostering a culture of transparency within the organization.

Darren Belisle

Indeed, the situation is challenging, but with collaborative effort-government, industry, and civil society-we can steer towards a more inclusive regulatory environment!

Moses Yeo

Collaborative effort sounds nice, yet history shows that bureaucracy often stalls progress; expect more hurdles before any meaningful change.

Richard Bocchinfuso

i think they r just scared of losing control, not really about money laundering.

manika nathaemploy

It’s understandable to feel that way; many people share concerns about over‑regulation and its impact on everyday users.

Debra Sears

Do you think the FATF pressure will finally push Bangladesh to draft a dedicated crypto law, or will they stick to the current patchwork?

Matthew Laird

Bangladesh should protect its sovereignty first; foreign pressure can’t dictate how we handle our own financial systems.

EDWARD SAKTI PUTRA

I hear the worries on both sides; finding a middle ground will be key for the country's economic future.

Jason Wuchenich

Remember, staying informed and compliant is the best strategy right now; keep learning and share knowledge with peers.

Mark Fewster

Regulation needs clarity, not confusion.